FRANKFURT.

There are less than two weeks left to see what I think might be the most marvelous and wonderful exhibit that I've seen in several years: The Architectural Model: Tool, Fetish, Small Utopia at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt. This fantastic show closes on 16 September.

One measure of how outstanding this show is would be to report that I left a Mediterranean beach a day early in mid-August, flew to Germany and spent the night, and the show was worth missing out on another day in the ocean and the substantial extra expense of making a dedicated trip to Frankfurt.

A mid-century German children's toy of a bank block.

A delightful series of peep-holes offered views into built and unbuilt worlds

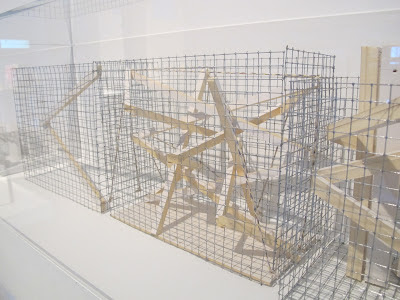

Another demonstration of the show's merits is to show here three-dozen or so images from the exhibit, which takes up three floors of the German Architectural Museum with a plethora of astonishing, inspiring, and simply gorgeous architectural models, from children's toys to presentation models, iterative study models to vast recreations of ancient monuments, rare proposals of never-built masterpieces, peep-hole views into far-off rooms and staggeringly detailed, person-sized skyscrapers.

Conrad Roland's drawing for an exhibition hall with floating levels, 1964

Conrad Roland's Spiralhochhaus, which incredibly was conceived in 1963.

Still mesmerizing: the original model for

Frei Otto's Medizinsche Fakultät Ulm, 1965.

Wolfgang Rathke's German Pavilion for the

Worlds Fair in Montreal, 1964-65, mode of pink straws.

Christian Kerez's unbuilt Swiss Re Headquarters in Zürich.

Detail of the table-size model of Arata Isozaki's Cluster in the Air, 1962

One of the more striking models in the whole exhibit:

Emilio Ambasz's design for the Center for Applied Computer Research,

Mexico City,1974-75

James Stirling's Churchill College proposal, Apr-May 1959

While these never-to-be environments, found on both the ground floor and the top, would alone make for a noteworthy exhibit, the second floor is particularly awesome: At model-railroad scales (most 1:200), the visitor can play bird, or god, hovering over the humungous dioramas of ancient, medieval, and modern landscapes, many of which turned to dust centuries before the helicopter. The room opens with the quintessential rotorcraft view: a frenetic five-block slice of mid-town Manhattan, bustling with taxis at the foot of the Pan Am Building and bending around Grand Central Station.

The Royal Crescent, Bath.

A busy day in central Pompeii

The acropolis at Mycenae

Temple of the Pharaohs, Dêr El Bahari, Egypt.

Bruchfeldstraße Housing Development, Frankfurt-Niederrad, 1926-27

The Baroque town of Arolsen, North Hesse as it appeared in 1719

An unfortunate moment of sorts occurs as the visitor returns to the stairwell: the last diorama shows an Orinocoan settlement, a ring-clearing in the forest constructed by the indigenous Yanoama culture, one of the few moments of non-Indo-European architecture in the whole exhibit. Having seen these mono-structural villages in anthropological texts, I can attest to their impressive monumentality imbued with spiritual reasoning, which juxtaposes quite well with the square of Pompeii nearby and the Valley of Egypt across the room.

Yet the accompanying wall panel merely assigns the Yanoama the word, "primitive" which is at best a thoughtless translation, and at worst a very unenlightened classification system for a German institution to be using to categorize various peoples of the world. The more ignominious connotations of this moment are ameliorated by the floor above, which give over ample space to the importance of models in Hitler's Reich, with photos, texts, and objects from the office of Albert Speer, and the like.

The village center, a clearing the rainforest, ringed by dwellings,

signature construction of the Yanoama,

and how these "Indians" are described on the wall label.

A placard explaining the fascist plan for Munich, 1939.

While there is plenty of text for student or professional visitors, cueing into process, explanations of formal evolution, struggling with formal idea to execution, the constraints of construction, material, and reality, these aspects can become a bit heavy and technical, especially for those viewers who associate foam and plywood with late nights in the studio. With such a large exhibit, the great number of items to view is itself overwhelming. The exhibit might be most enjoyable in the unfamiliar moments of a micro-vista or a lilliputian skyline, understanding its translation to scale and contemplating the possibilities it suggests. These are sensations of another world.

A stunning series of small foam creations.

It is a simple matter of a 15-minute walk from the museum, crossing the Main on foot to see this architectural moment in person. While the model's white foam pieces come alive in brick, stone and glass in the sunlight, the dynamic might of the tower's mass against the block and older offices is somehow lessened from the street. Yet this arrangement of masses is more familiar now. Having looked down, it is better understood. For a moment, you flew above it, and could hold a tower in your hand. But you are no longer flying. The imaginary helicopter has landed back on earth, in reality.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.