FRANKFURT.

There are less than two weeks left to see what I think might be the most marvelous and wonderful exhibit that I've seen in several years:

The Architectural Model: Tool, Fetish, Small Utopia at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt. This fantastic show closes on 16 September.

Visually describing a building evinces the possibility of another building

One measure of how outstanding this show is would be to report that I left a Mediterranean beach a day early in mid-August, flew to Germany and spent the night, and the show was worth missing out on another day in the ocean and the substantial extra expense of making a dedicated trip to Frankfurt.

A mid-century German children's toy of a bank block.

A delightful series of peep-holes offered views into built and unbuilt worlds

Another demonstration of the show's merits is to show here three-dozen or so images from the exhibit, which takes up three floors of the German Architectural Museum with a plethora of astonishing, inspiring, and simply gorgeous architectural models, from children's toys to presentation models, iterative study models to vast recreations of ancient monuments, rare proposals of never-built masterpieces, peep-hole views into far-off rooms and staggeringly detailed, person-sized skyscrapers.

Conrad Roland's drawing for an exhibition hall with floating levels, 1964

Conrad Roland's Spiralhochhaus, which incredibly was conceived in 1963.

Still mesmerizing: the original model for

Frei Otto's Medizinsche Fakultät Ulm, 1965.

Wolfgang Rathke's German Pavilion for the

Worlds Fair in Montreal, 1964-65, mode of pink straws.

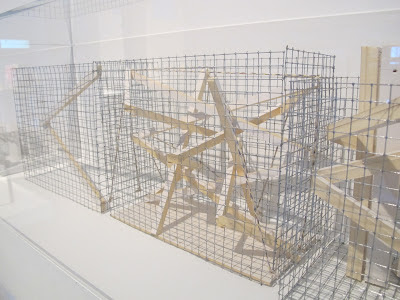

The ground floor snaps entering visitors to attention with a room-full of rare masterpieces, many of them brilliant visions which never were, interspersed with tabletops stuffed with mass and volume studies of foam and wood and preliminary designs whose forms are as adventurous and ingenious as their choice of materials such as the drinking-straw dome of the Montreal Pavilion proposal. These early-stage demonstrations continue of the top floor, such as the number of studies for Christian Kerez's unbuilt Swiss Re: Headquarters in Zürich, which reached its climax in a refrigerator-sized wooden assemblage of floors, beams, ramps, and stairs.

Christian Kerez's unbuilt Swiss Re Headquarters in Zürich.

These are just some of the hundreds of items that the exhibit has collected together, some from its own vaults, some rare gems borrowed from the archives of old masters. Together, these might roughly fall into three categories: those places which exist in the world (models of real buildings, but which give license to show an alternate reality both in terms of scale with view but also material and transparency); ancient places which exist no more, and so those models which are the best representation of what was once real; and those places which have never existed: whose closest realities are the models themselves. Highlights include the tabletop hypermetabolist landscape of Arata Isozaki's Cluster in the Air to the smaller but equally wondrous proposal by Emilio Ambasz for the Center for Applied Computer Research, an unrealized Digital-Aztec precinct on the outskirts of Mexico City.

Detail of the table-size model of Arata Isozaki's Cluster in the Air, 1962

One of the more striking models in the whole exhibit:

Emilio Ambasz's design for the Center for Applied Computer Research,

Mexico City,1974-75

James Stirling's Churchill College proposal, Apr-May 1959

While these never-to-be environments, found on both the ground floor and the top, would alone make for a noteworthy exhibit, the second floor is particularly awesome: At model-railroad scales (most 1:200), the visitor can play bird, or god, hovering over the humungous dioramas of ancient, medieval, and modern landscapes, many of which turned to dust centuries before the helicopter. The room opens with the quintessential rotorcraft view: a frenetic five-block slice of mid-town Manhattan, bustling with taxis at the foot of the Pan Am Building and bending around Grand Central Station.

This bustle contacts with the eerie serenity of the other scenes nearby. In the whole exhibit there might be nothing so incredible a visual experience as standing alone above these landscapes of the never-more. Of all these, the lone model of the Crystal Palace presented the most jaw-dropping surprise. Even at the scale of an insect, the enormity of its enclosure is arresting, its relentless frame disappearing into the scene's dark far edge, as if it emerged from the blackness of lost history for the brief instant of this installation.

The Royal Crescent at Bath next door is similarly isolated yet, given its history, less forlorn. The other dioramas of even older times, stretching back all the way to Mycenae and Rome, Egypt and Sumeria, are not at all melancholy, but delightful and breathtaking. These might be more common in history or anthropology museums, if not toy emporiums, and certainly not in galleries of architecture, which is precisely one of the main reasons which its so refreshing to have the heart of the exhibit given over to such "popular" and non-academic displays.

The Royal Crescent, Bath.

A busy day in central Pompeii

The acropolis at Mycenae

Temple of the Pharaohs, Dêr El Bahari, Egypt.

Bruchfeldstraße Housing Development, Frankfurt-Niederrad, 1926-27

The Baroque town of Arolsen, North Hesse as it appeared in 1719

An unfortunate moment of sorts occurs as the visitor returns to the stairwell: the last diorama shows an Orinocoan settlement, a ring-clearing in the forest constructed by the indigenous Yanoama culture, one of the few moments of non-Indo-European architecture in the whole exhibit. Having seen these

mono-structural villages in anthropological texts, I can attest to their impressive monumentality imbued with spiritual reasoning, which juxtaposes quite well with the square of Pompeii nearby and the Valley of Egypt across the room.

Yet the accompanying wall panel merely assigns the Yanoama the word, "primitive" which is at best a thoughtless translation, and at worst a very unenlightened classification system for a German institution to be using to categorize various peoples of the world. The more ignominious connotations of this moment are ameliorated by the floor above, which give over ample space to the importance of models in Hitler's Reich, with photos, texts, and objects from the office of Albert Speer, and the like.

The village center, a clearing the rainforest, ringed by dwellings,

signature construction of the Yanoama,

and how these "Indians" are described on the wall label.

A placard explaining the fascist plan for Munich, 1939.

While there is plenty of text for student or professional visitors, cueing into process, explanations of formal evolution, struggling with formal idea to execution, the constraints of construction, material, and reality, these aspects can become a bit heavy and technical, especially for those viewers who associate foam and plywood with late nights in the studio. With such a large exhibit, the great number of items to view is itself overwhelming. The exhibit might be most enjoyable in the unfamiliar moments of a micro-vista or a lilliputian skyline, understanding its translation to scale and contemplating the possibilities it suggests. These are sensations of another world.

A stunning series of small foam creations.

One particularly large display on the second floor is Foster and Partners' presentation model of the Commerzbank, one of hometown Frankfurt's most well-known skyscrapers. From this

Vogelperspective, the tower still soars above the tops of heads, but the vantage point allows a view into the diminutive courtyard created by the successive arrangement of buildings of various heights and vintages, all dwarfed by the massive bank, which seems to have carved out a space in the air.

It is a simple matter of a 15-minute walk from the museum, crossing the Main on foot to see this architectural moment in person. While the model's white foam pieces come alive in brick, stone and glass in the sunlight, the dynamic might of the tower's mass against the block and older offices is somehow lessened from the street. Yet this arrangement of masses is more familiar now. Having looked down, it is better understood. For a moment, you flew above it, and could hold a tower in your hand. But you are no longer flying. The imaginary helicopter has landed back on earth, in reality.