BAGHDAD.

I just finished reading Eric Bennet's extraordinary work of fiction, A Big Enough Lie, published last year. I highly recommend it. Bennet is a very gifted writer, with a unique voice and remarkable talents with language. In particular, I was struck by his passing descriptions of the Iraq of a decade ago, where much of the most consequential action in the book, scenes from the U.S. occupation, takes place.

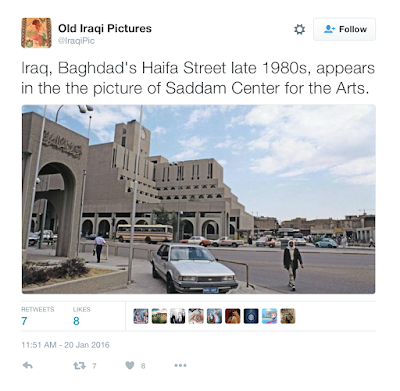

Within about 24 hours of finishing the novel, I learned about the Twitter account Old Iraqi Pictures, which also launched about a year and half ago, featuring photography going back over a century of the country's cities, archaeological sites, architecture, street scenes and people. The site has also posted photos from the U.S. Invasion itself. Scrolling through the account's posts brought Bennet's aggressive and dismal descriptions of the assaulted, occupied, threatening urban ruin to an even more poignant horror.

Here are a few of the most vivid passages, juxtaposed with a sampling of Old Iraqi's archives. Read the book and check out the Twitter feed (most of the images below link to the original Tweet).

Camp Triumph...filled an island on the Tigris where, until last year, an amusement park had entertained Ba'ath Party members and their children. Three months ago Iraqi mortars knocked the Ferris wheel flat on its side, crushing an E2. I had been there. Concrete cartoon mice, twice as large as men, grinned at the dead soldier.

We passed modern high-rise with massive concrete flutes dotted with satellite disks like fungi on industrial logs The shops surrounding lay in ruins. I studied heads in passing cars. Boom. That's what you were always thinking, Boom. At intersections during the past few months the kids had stopped waving and smiling; the men had never waved or smiled. Boom.

We reached the four-meter high walls that divided chaos from order, poverty from wealth, heat from AC, anarchy from democracy, the dystopia of Iraq from the utopia of the States, the streets of Baghdad from the Green Zone.

When I opened my eyes again it was not because the sun was up. Outside the window a skyline of palm trees and biblical-modernist architecture loomed in dark indigo against dark-blue sky.

We drove down safe broad streets empty with dawn. We passed the Republican Palace, from each corner of whose magnificent edifice a head of Saddam survey his lost empire. "Saddam wrote novels," I said.

"In blood" Greep said.

"About reclaiming the glory of Babylon."

We drove around until we found the Al-Rashid Hotel...The dark atrium of the convention center exuded 1970s affluence, but that was transformed by two decades of war and impoverishment...In those years blunt facades, perpendicular lines, gold railings, square chandeliers, and sepia windows had struck Iraqis as the best possible instantiations of vast wealth...

The atrium looked like a student union at a declining state university in midsummer. Printed sheets of PowerPoint slides cluttered the square column and directed visitors to various offices: 'The Iraq Mine Action Center," 'The Dutch Liaison Office to the CPA," " The Iraqi American Friendship Council," "The Royal Jordanian Airlines ticket Office," "Office of Infrastructure" and so on.

The streets stretched before us in sick green. The hellishness of the city at nigh tyrannized your nerves. I never hated a place as I hated Baghdad. Sometimes I tried to imagine living here in a time of peace, to picture what kind of happiness you could hope for. The rank smells, the high heat, the oppressive architecture...the beleaguered palms and rutted streets, the angular meretriciousness of the 1970s architecture tarnished by twenty years of war—it was unbearable every aspect.